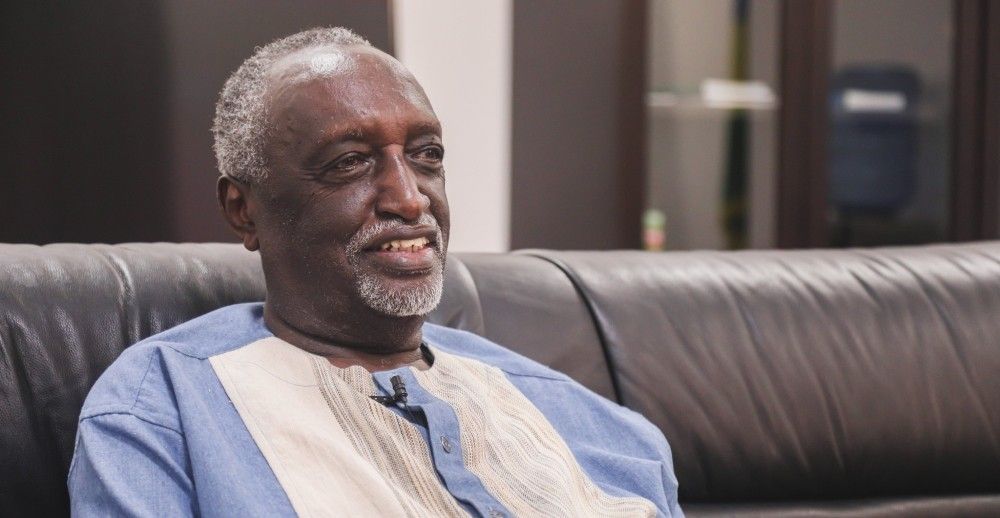

When Hon. Tito Rutaremara speaks about colonialism, his words carry the weight of history. It is not the history of distant wars or nameless kings, but that of a nation interrupted, its heart torn from its body, its soul rewritten in foreign ink.

To him, colonialism did not just conquer Rwanda, it dismantled the idea of being Rwandan itself. “Rwanda did not lose because we were weak. We lost because we were divided, and because the invaders came with knowledge of how to destroy us from within,” he says.

Before the Europeans came, Rwanda was not the blank slate that colonial textbooks would later describe. It was an organized, disciplined nation-state, an empire built on structure, unity, and moral code.

Its people lived by taboos that safeguarded integrity, respect, and order. Kings ruled under sacred oaths, guided by the counsel of the guardians of tradition and wisdom.

But when the colonizers crossed into Rwanda in the late 19th century, they found a nation wounded by its own internal strife. The death of King Rwabugiri had left behind a power vacuum. His sons, Musinga and Rutarindwa, became enemies.

Their rivalry culminated in what historians call the Coup d’État of Rucunshu, a turning point that fractured Rwanda’s unity. “Division became our greatest weapon against ourselves. The colonizers did not have to fire many bullets, they found us already bleeding from within,” Rutaremara recalls.

At the time, the Europeans came armed with cannons, rifles, and knowledge of Africa’s terrain. They had already subdued neighboring kingdoms like Karagwe in present-day Tanzania. When Rwandan envoys sought advice, Karagwe’s rulers warned them that the Europeans had weapons that could destroy their army.

By the dawn of the 20th century, Rwanda’s sovereignty had fallen, not through a grand battle, but through manipulation, isolation, and the calculated dismantling of its systems. Letting them in was a fatal miscalculation.

Unmaking the nation-state

Once colonial rule took hold, Rwanda’s carefully woven institutions were torn apart thread by thread. The king was stripped of authority, the royal army dissolved, and the traditional schools that shaped warriors and leaders (amatorero) were banned.

The rituals that once symbolized continuity between generations were outlawed, and the keepers of sacred knowledge (abiru), were exiled. “The colonizers understood that to dominate a people, you must first erase their memory. They replaced our gods, our greetings, even our sense of morality,” Rutaremara explains.

In place of Imana, the ancestral God, came Mungu, the foreign deity introduced through Christianity. The traditional greeting of mutual respect was replaced with “Yezu akuzwe” (Praise Jesus). The colonizers built churches where shrines of Nyabingi and Ryangombe once stood, branding ancestral worship as evil.

They forbade initiation rites (kubandwa) and offerings to ancestors (guterekera), ordering Rwandans instead to learn catechism and baptism. They changed how Rwandans saw themselves and began to worship what was foreign. “In their eyes, civilization meant forgetting who we were.” Rutaremara laments.

Even Rwanda’s governance was reduced to a colonial afterthought. At the top stood the King of Belgium, then the Minister of colonies, the Governor-General in Léopoldville (Kinshasa), the Vice-Governor in Bujumbura, and finally, the Resident in Kigali. Only after all these layers of foreign authority came the Rwandan king, powerless and symbolic.

“Rwanda became smaller than a Belgian district and that was the death of Rwanda as a nation-state,” Rutaremara notes.

The colonization of the mind

If the dismantling of Rwanda’s institutions broke its body, the colonization of its mind shattered its soul. Traditional education was replaced by missionary schools.

The oral literature and poetry that once celebrated heroism and wisdom were silenced. Rwandans were taught not to think in Kinyarwanda, but to think in borrowed languages and borrowed logic.

“We were left wishing to think like Europeans, but we couldn’t. We were left wishing to become Europeans, but we failed. So what did we become? It was not only a rhetorical question, it was a challenge,” Rutaremara reflects with quiet pain.

Today, Rutaremara, one of Rwanda’s most seasoned political thinkers and among the architects of the country’s post-genocide reconstruction, believes the struggle for independence was not just about reclaiming land or sovereignty. It was about restoring dignity, the ability to think, live, and lead as Rwandans again.

“The real liberation is the liberation of the mind. Once you think like a free person, no one can ever colonize you again,” he insists.

Reclaiming the soul of a nation

Modern Rwanda bears the scars and lessons of that painful past. The institutions that were once dismantled have been rebuilt with renewed purpose. The values that were erased (unity, integrity, hard work) are now enshrined in the nation’s development philosophy.

Rutaremara believes that understanding the wounds of colonialism is key to understanding Rwanda’s resilience today. “We do not seek to rewrite history but to reclaim it, to remind our children that Rwanda was once whole and can be whole again,” he says.

His reflections are not about bitterness, but clarity. In his eyes, remembering is not dwelling in the past; it is ensuring that Rwanda never again becomes a colony, politically, economically, mentally or otherwise.

“When we lost our civilization, we lost our mirror. Today, we are rebuilding it piece by piece, to see ourselves again clearly, proudly, and as Rwandans,” he reaffirms.