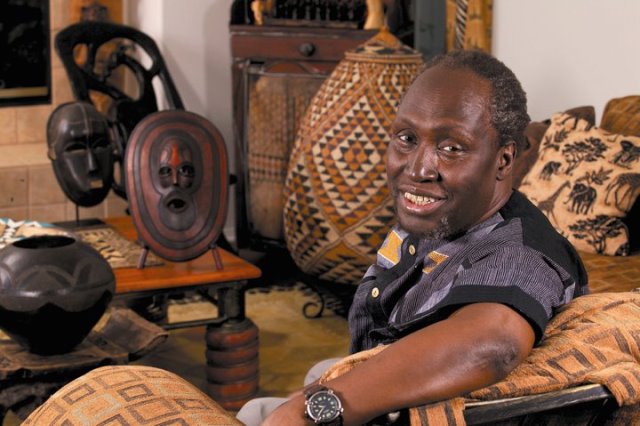

In the quiet hours of May 28, 2025, Africa lost not just a man, but a voice — a fierce, unwavering voice that echoed across continents and generations. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the Kenyan writer, intellectual, and conscience of a decolonising continent, passed away at the age of 87.

From the red soil of Limuru, Kenya, where he was born in 1938 as James Ngugi, to global lecture halls and village theatres, Ngũgĩ carved his path with ink and indignation. He changed his name in the 1970s to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o — a bold renunciation of colonial chains — and never looked back. His life was a story of exile and return, of struggle and scholarship, of words as weapons and language as liberation.

His son, writer and academic Mukoma wa Ngugi, broke the news to the world with solemn reverence, describing his father not merely as a parent, but as a prophet. “My father’s life was a life in service of language, of memory, and of justice,” he wrote. “He lived the very ideas he wrote about — courageously, defiantly.”

Indeed, Ngũgĩ’s pen bore witness to Africa’s traumas and triumphs. His early works — Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967) — formed a literary trinity that would establish him as the chronicler of Kenya’s colonial past and its troubled emergence into nationhood.

But it was his radical turn — both political and linguistic — that marked Ngũgĩ as something greater than a novelist. With Petals of Blood (1977) and the revolutionary play Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”), co-authored with Ngugi wa Mirii and staged by peasants in his home village, he denounced neocolonial corruption and capitalist betrayal with fearless clarity.

For this, the Kenyan government imprisoned him in 1977 — not for weapons or treason, but for wielding truth too eloquently. In prison, he wrote Devil on the Cross (1980) in Kikuyu on toilet paper — a triumph of spirit over repression and the first modern novel in that language.

Ngũgĩ believed that language is memory, and memory is identity. In his seminal essay collection Decolonising the Mind (1986), he exhorted African writers to write in their mother tongues, not the tongues of their former masters. “Language is both a means of communication and a carrier of culture,” he wrote. It was a manifesto that sparked literary rebellions and reshaped curricula from Nairobi to New York.

He went on to write deeply philosophical and personal works like Something Torn and New (2009) and Birth of a Dream Weaver (2016) — a memoir of his Makerere University days, where the seeds of political consciousness first bloomed.

His teaching career spanned Yale, NYU, and the University of California, Irvine, where he was Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature. Yet his classroom was far larger: the continent itself, and the diaspora it birthed.

Tributes from Across the Globe

Kenya’s President William Ruto hailed Ngũgĩ as “a towering figure in African literature” whose words “helped shape the moral and intellectual foundation of the Kenyan nation.”

Human rights advocate Maina Kiai, reflecting on being expelled from school for staging one of Ngũgĩ’s plays, said: “He taught us that art can be revolution. That truth cannot be caged.”

Across the Atlantic, literary scholar Prof. Carole Boyce Davies described him as “the moral compass of postcolonial African letters.”

Saisi Marasa, President of the Kenya Diaspora Alliance, called Ngũgĩ “a prophet whose pen pierced empires.” For Mkawasi Mcharo, “he was Africa’s unrepentant voice of memory.”

“Ngũgĩ’s vision of storytelling as an act of healing and reclamation has inspired our own writers and thinkers to look inward, and then outward, with clarity,” said a Rwandan academic in tribute.

An Eternal Voice

Ngũgĩ’s work was nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, an honor many believed he richly deserved. Yet he needed no laurels to ascend into immortality. His voice endures — in every African child taught to cherish their mother tongue, in every writer who dares to defy authority, in every story that dares to remember.

He is survived by his children, including Mukoma, and a world profoundly changed by his vision.

In the words of A Grain of Wheat, one of his most haunting lines lingers now with final weight:

“A man lives on through his work.”

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o lives on — not merely in memory, but in every story still waiting to be told in freedom.